7 Quai du Commerce, a place of passage and exchange

Donatienne de Séjournet

11th—15th century

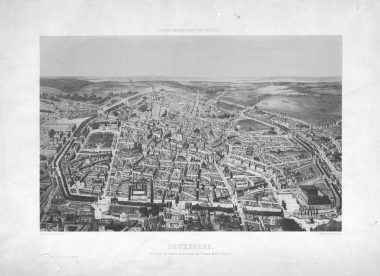

In the eleventh century, Brussels was still a small town in the middle of a marshy valley. It was connected to the North Sea by a small, slow, and capricious river: the Senne. A port allowed for the unloading and weighing of cargo. Initially, a makeshift dock downstream from the Île Saint-Géry, the port expanded during the Middle Ages into a quay, called the werf, near the old Saint-Catherine’s church where a crane and a public scale were installed. Becoming very cramped in its first enclosure dating from the thirteenth century, new fortifications were built to strengthen the city’s defense a century later. About seventy semicircular towers and seven gates mark the 8 kilometers of wall and ditch of the second enclosure encompassing the city and its suburbs. The current 7 Quai du Commerce sits atop what was the wall which divided the city from the countryside, with embankments on both sides of the structure.

16th—17th century

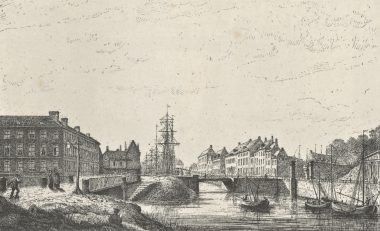

River traffic on the Senne was fraught with difficulties and hampered by staging rights and rivalry between trading cities, which were detrimental to the commercial prosperity of Brussels. After bitter negotiations between the inhabitants of Brussels and Mechelen, the opening of the Willebroek Canal in 1561 gave Brussels direct access to the port of Antwerp via the Rupel and the Scheldt, and led to the creation of a new district that stretched to the heart of the city. The ramparts of the second wall were given a new fortified gate, called the Porte du Rivage. The digging of the Bassin des Marchands and Bassin des Barques was followed by that of the Bassin Saint-Catherine, which took the place of the disused ditch that had belonged to the first enclosure. Warehouses, wholesalers, and inns were built along the quays. Two additional docks were also built: the Manure dock or “Mestbak” to evacuate the city’s garbage, and the Hay dock to build new warehouses and hay sheds. Near the stately Porte du Rivage, a gate known as the “Porte des Vaches” was built into the wall to let the cattle in and out of the Grand Béguinage, and to allow sailors to reach the modest shipyard on the other side of the moat from the Quai au Foin. William the Silent used this passage and the Impasse des Matelots clandestinely, in order to escape the oppression of the Duke of Alba. The alley, now reduced by half, allows access to the back of 7 Quai du Commerce.

18th century

The Port of Brussels was the heart of the city’s economic life. While opulent mansions rubbed shoulders with small gabled houses, factories were established alongside trading houses and warehouses to take advantage of the waterway. All merchandise passed through here. Under the control of the merchants, sailors and handlers were busy loading or unloading the cargo of the ships docked at the quays, whose names still evoke the diversity of products and materials. There was a lively activity with the comings and goings of carts and the cries from the fish market, while travelers waited for their departure to Vilvoorde, Mechelen, or Antwerp in front of the boathouse located in the Rue du Marché aux Porcs, opposite the Cheval Marin. In 1781, at the end of the Quai au Foin, the first public warehouse was built. In the nineteenth century, architect Jean Baes transformed it to welcome the Flemish Theatre.

1810

On May 19, Napoleon ordered the demolition of the second city wall and its replacement by grand promenades and boulevards, which the engineer and architect Jean-Baptiste Vifquain developed thanks to the enthusiasm of the new sovereign, William I of the Netherlands. It was during this Dutch period that the Charleroi Canal was also built, linking the mining city to Brussels. The Willebroek Canal was widened and the port enlarged on the grounds outside of the old ramparts, giving the district a new lease on life.

1820

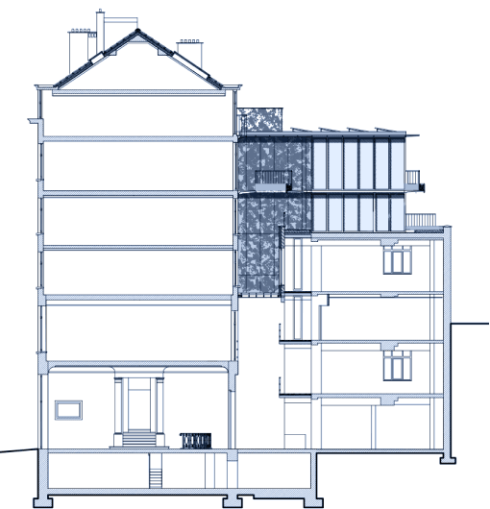

The dismantling of the ramparts and the layout of a new quay, the future Quai du Commerce, freed up land for development. In August, engineer Frédéric De Ridder, a relative of Jean-Baptiste Vifquain, submitted a permit for the construction of four palace-like tenement houses with long, sober, neoclassical facades, at 5, 7, 9, and 11 Quai du Commerce.

1830

On April 3, from the balcony of the 7 Quai du Commerce, workers could be seen laying the foundation stone of the new Bassin du Commerce, in the presence of the mayor of Brussels. They dug an inner port of about 180 meters long between the Bassin des Barques and the Boulevard d’Anvers on the Plaine du Chien-Vert. It links with the recent Bassin du Chantier, which was used for careening ships. Only its eastern bank is an actual quay; the other bank is a vast customs warehouse by architect Louis Spaak. This Grand Bassin gradually replaced the old port. Saint Catherine’s Dock was filled in around 1850 to allow the construction of a new church by Joseph Poelaert. From then on, 7 Quai du Commerce was occupied by the Finets, a family of customs agents, and then by the Fontaines, who were fabric suppliers.

1870

Activity around the Bassin du Commerce was so intense that it was difficult to move around the docks, which were clogged with foodstuffs and building cargo. Two to three hundred ships from abroad unloaded 25 to 30,000 tons of goods each year, while a procession of overloaded barges circulated daily between the interior canals. To cope with this flourishing trade, the owner of the building, Léonard Mommaerts, built an annex in the courtyard of 7 Quai du Commerce for his new tenant, Victor Washer, a trader in canned food, dried fruit, wine, and beer. From 1885 to 1908, Mommaerts handed over the premises to a customs and excise administration, also linked to the port activity.

1910

In order to respond to the increase in river transport, which required the modernization of maritime infrastructure, Brussels built a new port outside the Pentagon. The inner docks were filled in and replaced by wide avenues whose names alone retain the memory of the old quays. As for the Bassin du Commerce, it gave way to the boulevards of Ypres and Dixmude, as well as to the Square Sainctelette. The Quai du Commerce became a wide, shaded avenue, with buildings only on one side.

1920

The rebound of the postwar real-estate market gave a new dynamism to the district, where a series of Beaux-Arts and Art Deco-style apartment buildings were built, along with studios, shops, and warehouses, as well as a few small factories such as Charlet & Cie at the corner of Quai du Commerce and Place de l’Yser. The even side of the quay began to develop, and eventually the Gondrand brothers from Milan, who had sixteen other offices in Europe, set up their international transport office and warehouses in the ideally located ground floor of 7 Quai du Commerce.

1927

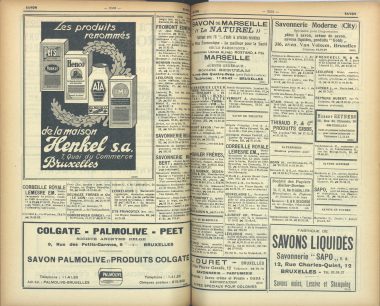

There was a concentration of wholesale trade in the district, which maintained the old port’s commercial tradition. 7 Quai du Commerce was no exception, but it needed larger warehouses. Its new owner, Jules Nerinckx, who lived nearby on the Boulevard d’Anvers, undertook major renovations for nearly three years. He raised the building by two levels in order to accommodate stores and wholesale offices on the ground and first floors, and apartments on the top three floors. The facade, decorated with sober moldings, was adapted to current tastes while a three-story building was built in the courtyard. At the back, an exit allows access to the Impasse des Matelots. Once the work was completed, the textile wholesalers Levy Frères & Co. moved in, followed by Henkel, the now well-

known German soap and detergent manufacturer.

1940

On May 28, Belgium surrendered to the German forces. Three months later, 7 Quai du Commerce was assigned to the UFA, one of the most prominent German film production companies. The nearby Gare du Nord station made it easy to receive short and feature-length films from Berlin, propaganda that the film company had to promote and distribute in all Belgian cinemas. Subject to the strict control of the Propaganda-Abteilung Belgien, Belgian cinemas were forbidden from showing American and English films in favor of German and Italian productions, and they were obliged to preview the new films supplied by the UFA before each screening. Camille Damman designed a projection room and booth as well as a reinforced concrete shelter, a bona fide blockhouse for storing film reels.

1945

Following its demise in September 1944, the UFA left a great deal of material that was sequestered, like other German film companies. 7 Quai du Commerce became the headquarters for the management of this procedure. Part of its stock was moved to the Ministry of National Education’s film department and, following a fire at the Ministry, the whole department moved to 7 Quai du Commerce in 1949 and began to carry out its mission of providing educational films and teaching materials to schools in Belgium. Audio visual material on film, on 78 and 33 rpm records, then later on magnetic tapes were sent to schools from 7 Quai du Commerce. During the renovations, hundreds of records were found in the attic.

1970

The fracture within the urban fabric caused by the North-South railway axis, the growing pragmatism of the services economy, and the excessive use of private cars, led to the alienation of the historic districts of the city center, sacrificing the buildings to tourism despite their deterioration. While the old port could not escape this, the commitment of its inhabitants later led to its revitalization, the renovation of the Béguinage district, and

the redevelopment of the quays at the end of the 1970s.

2000

The Joint Community Commission of the Brussels-Capital Region took possession of 7 Quai du Commerce, which had passed from the Ministry of National Education to the Flemish Community as part of the regionalization of Belgian institutions. Various associations and platforms in charge of mental health established their offices in the building. Among them, the nonprofit Rivage-Den Zaet, which occupied the first three floors, converting them into several medical offices and waiting rooms for psychiatrists and psychologists for local people in need. The public platform in charge of mental health for the Brussels region occupied the upper offices.

2020

While retaining the character of a working-class neighborhood where a multicultural mosaic now coexists, the former port has been transformed as a result of the gentrification of the Dansaert district, which became a trendy and fashionable neighborhood in the late 1980s. Through this evolution, the district became a melting pot of innovative and multidisciplinary artistic initiatives. In the area you can find the theater La Bellone, the galleries Greta Meert and dépendance, and Centrale for contemporary art, an art center in an old power station. This cultural flourishing was later reinforced by the creation of MIMA and KANAL – Centre Pompidou. After being purchased at public sale in late 2015, the building underwent a major renovation that keeps in line with its history. In 2021, a new chapter of history for 7 Quai du Commerce begins at the intersection of trade, culture, and communication.

![Square Sainctelette in Brussels (Quai du Commerce at the corner of Boulevard d’Anvers on the left], postcard, 1930–1934 / published by Nels. City Archives, Brussels, inv. W-9446. Photo credit:](https://test.cloudseven.hellomarcel.be/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/1920_AVB_CI_W_09446-380x241.jpg)