Alighiero Boetti as « Ghost Curator »

Christine Jamart discusses the exhibition Inaspettatamente (Unexpectedly) with Frédéric de Goldschmidt and Grégory Lang

The work of Alighiero Boetti (1940–1994), which Frédéric de Goldschmidt discovered in the exhibition Magiciens de la terre in 1989, is exceptionally singular and eschews all trends. Bernard Blistène once said of the Turinese artist that his practice was a “continuous experience,” which keeps it topical. He distanced himself early on from Arte Povera, and developed a deep interest in press and communication networks (newspapers, photocopiers, mail art, etc.). His mutable writing takes pleasure in seriality and the processes of imprinting and permutation. The language is poetic, cryptic, and made of paradoxical and tautological word games. Boetti dismantled the notion of authorship and set up processes of delegation, notably through works of political cartography carried out in Afghanistan, which brought him a new level of international recognition. Inaspettatamente (Unexpectedly), a small embroidery from 1987 hanging on de Goldschmidt’s walls, lends its name to the inaugural exhibition of the new space he is opening in the heart of Brussels. This conversation took place in the room in which he is in the process of finalizing the show with curator Grégory Lang.

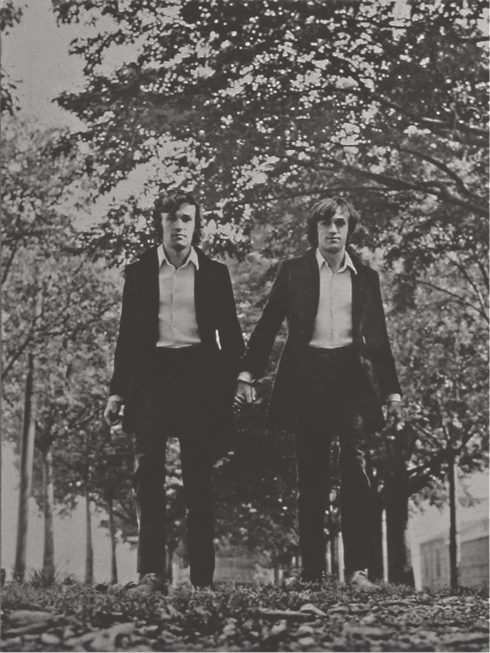

GL: After a detailed analysis and objective reading of Frédéric’s collection, Alighiero Boetti appeared to be the most represented contemporary artist, along with the ZERO group. The works from ZERO group gathered by Frederic had already been a source of inspiration for an exhibition I curated at the FRAC Grand Large in Dunkirk. On the other hand, Boetti’s work has always captivated me; he left behind an air of mystery as he traversed our recent period of art history. His elusive and prolific work speaks to everyone, through both its precise concepts and the plurality of modes of perception. The figure of Boetti evokes above all a state of being linked to his personality, which Harald Szeemann put on display in the iconic exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form in 1969.

FG: I really like exhibitions curated by artists such as Danh Vô’s exhibition at the Punta della Dogana in Venice in 2015 2. There he exhibited with his friends, without wanting to be exhaustive on a theme. And Alighiero Boetti is certainly the only artist in my collection—and one of the few in the history of art—to have tackled so many themes and techniques. It allowed us to go in many different directions. I wanted the show to feel as if it had been curated with the inspiration of an artist with the professionalism of a curator.

GL: It was tempting to rely on an artist who had also experimented with different modes of production. It quickly became clear that the collection should be explored through the prism of both the themes of the works and Boetti’s personality. Groups of works already echoed this, either in a direct thematic connection or on a more intuitive level. The mental process of selection by assembly, association, and cognition could then begin.

CJ: How did you go about defining the various themes addressed in Inaspettatamente and selecting the corresponding works?

GL: We started by going back to Boetti’s work and (re)reading the catalogue texts. His work involved perception, attention, memory, language, reasoning, and a certain form of spirituality. We listed all the themes Boetti addressed, such as seriality and order/disorder, and tried to identify artists and works in the collection that were clearly in line with them. We realized that many of the pieces resonated with several of these axes. I put together sets of works that explored and expanded each of the themes. I printed visuals, collated them on the floor in groups, and captured them in their physicality in order to visualize the different ways they coexist and to specify how they might visually connect to one another. The idea was to create dialogues and narratives through their aesthetic and conceptual proximity. From this process, emerged a new and more nuanced interpretation of those initial themes. I lived with these compositions for a while, going over them several times before making proposals to Frédéric.

FG: Many of my pieces Grégory knew quite well, but he also had to dive, alone or with me, into my database to discover and understand all the others.

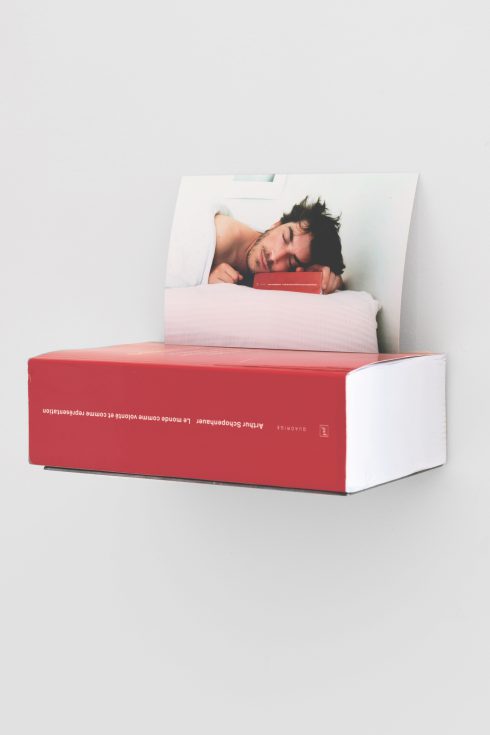

GL: The research on the database, which was still being organized, was indeed essential. But in order to understand the works’ full potential for the exhibition, I needed additional information, and also to ask Frédéric about unlisted works or those represented by only small thumbnails. Frédéric himself suggested works that I didn’t know about, or whose connections I didn’t suspect when visiting his storage space, and thus I discovered new links and gradually consolidated a group of works to be shown. When a collector shares his discoveries and his favorites with you, you have to experience it as well. It is a maieutic process that leads to certain selections for the exhibition. Hence, the importance of a collector’s formidable memory, its transmission and its mediation. Beyond the link to Boetti, the intention of Inaspettatamente is to reflect the diversity and complexity of the collection by sharing its historical pieces, a field in which Frédéric, better known for his support of the emerging scene, is an unexpected player. There are many artists and works that we would have liked to include but couldn’t. We always wanted to give priority to the most relevant work, the ones that resonate most within the context. In order to inhabit and give structure to the project, we first associated one of Boetti’s pieces from the collection with each theme. Since these were interchangeable, we had to navigate between several options. I had in mind to immerse myself in his universe and to evoke it in the space, the conceptual conversation, and the vibration between the works. But Frédéric gradually brought in this idea of summoning him as an interlocutor in his own right …

FG: He was our “ghost curator.” At any hesitation, we asked ourselves: “What would Boetti think?” Without a ceremony or incantation, he was our facilitator in a process of arbitration between two pieces, the integration (or not) of a work. Despite our criteria, we were keen on an approach that was not fixed, but fluid and responsive.

CJ: So, with Boetti’s almost spectral presence, even playing an active role in the process of designing and mounting the exhibition, could he be considered a co-curator?

GL: It truly was a bonus to invoke a deceased artist for this mission of exploring the collection; to walk with a guiding figure as I had done in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen collection in Rotterdam in dialogue with James Lee Byars. But here, indeed, we challenged ourselves to consider Boetti as a co-curator. One could say that we did this project in a state of mutual attention and understanding with him. Because chance and a certain latitude of interpretation played an essential role in his approach and practice, Boetti’s involvement was even easier. He himself did not hesitate to integrate the participation of others in the production process, be it friends, craftsmen, visitors, or other artists and curators.

FG: I also think that Boetti would have liked the exhibition to be held in a place like 7 Quai du Commerce that used to house psychiatric consultations. The dyad reason/madness was part of his admittedly dual but harmonious vision of the world where right and left, order and disorder, body and mind are all necessary. Like many artists in the 1960s, Boetti claimed a right to irrationality in an overly rational world. And to schizophrenia when he called himself Alighiero e Boetti, simultaneously distinguishing and linking the public side of his artistic personality with the intimacy of his first name. He did the same when his creative concepts were put into practice by others.

CJ: Can we talk about the process of delegation in curating?

GL: This aspect of sharing and delegating in curating, and therefore of letting go, is part of a deliberate configuration and process. It is a real state of mind only made possible by a degree of acuity and focused attention toward each work. When we would question one another and double check each other’s input, it was always done with benevolence and in the interest of the project. I often prefer co-curating and have had the opportunity to practice delegated curation by following artists’ protocols. I’ve interpreted and carried out their instructions for the exhibition Modus Operandi at Société in Brussels in 2017, following the projects developed by Art by Telephone … Recalled.3 Inaspettatamente transverses the different temporal experiences inherent to a curatorial triumvirate. The cumulated time Frédéric took to consider the works was of course longer, as it included and even preceded the moment of acquisition. Even if he doesn’t realize immediately the extent of a work’s meaning and potential, he’s always eager to find out more about it. He has a very personal and sensible way of getting involved with the work, of talking about it. Discovering one of his pieces in his company is like opening an emotional drawer. My research process involved questioning, remembering, visualizing of possibilities, and manipulating of the display of the work in a 2D or 3D space. Then comes the time to synthesize and assemble a cohesive whole. Boetti’s participation in the process is more fortuitous. His presence brings time into question: the timing of the obvious, of coincidence, of meeting at the right moment, of timeliness, of daydreaming, and also of the time it takes for an idea to come to mind and mature. This fluid model of decision-making is based on openness and trust in each other’s choices, or otherwise on suggestions to explore possible new combinations and configurations, and in turn to determine a course of action.

CJ: What about the title of the exhibition, apart from the fact that it comes from a work by Boetti in the collection? What does “unexpectedly” refer to here?

FG: When we were looking for a title, it was tempting to choose one of Boetti’s works, and for a long time we thought of calling it Zig Zag, after the oldest and probably most important piece of his that I own (which is on the cover of this book). But we chose Inaspettatamente, the title of this small arazzo (tapestry in Italian) hanging right here. It means “unexpectedly.” Not only does it rhyme with Not Really Really, the first exhibition at 7 Quai du Commerce before the renovation; it also suggests an approach, a way of looking at the collection itself that is not what could have been expected. There is a bit of second degree.

GL: We did not choose to confront works with the sole aim of creating unexpected relationships of tension between them. Rather, the unexpected comes from exploratory fields and typologies of works that are sometimes less obvious, which comes as a result of Frédéric’s interest in continuously discovering new work. Finally, the unexpected lies simply in the fact of presenting pieces that have never been exhibited nor associated with each other. It signals the overrepresentation of recognized artists in comparison to those young or emerging artists that Frédéric likes to collect.

CJ: Five years ago, Frédéric, you were mainly presenting young artists working with everyday objects. Your approach here is very different. Did you take the liberty of selecting pieces that have already been exhibited?

FG: There is a clear and affirmed difference in style between the two exhibitions held five years apart. We have indeed preferred to avoid duplication, however without prohibiting it. We also tried to give priority to pieces never shown in other exhibitions of my collection. Not Really Really and Inaspettatamente only have three pieces 4 and twenty artists in common, out of eighty-five works for the first one and three hundred and fifteen for the second. This amounts to four hundred works spread between the two exhibitions, which took place in the same building. Five years have passed since Not Really Really, so we wanted to take a different approach guided by a notably different style. The 2016 exhibition was about materials, about methods, while the works themselves would address disparate themes. Here, in 2021, we are rather focused on themes while the works embody very different styles and techniques.

CJ: Could you comment on the major themes from Boetti’s work that you identified and put in resonance with other historical and contemporary artists in the exhibition?

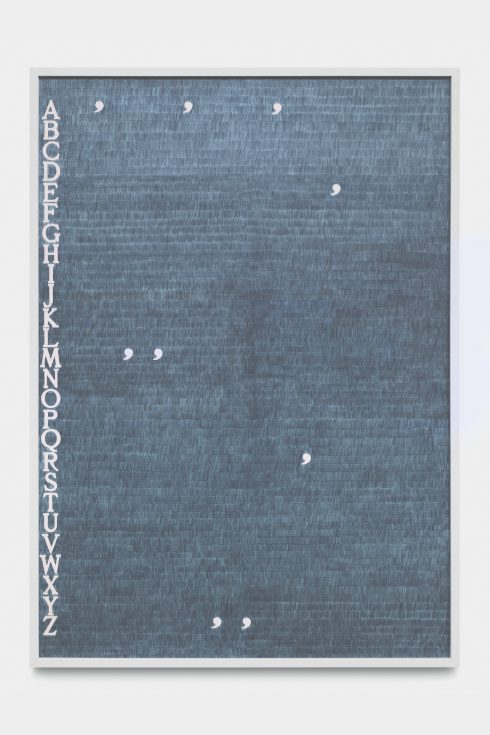

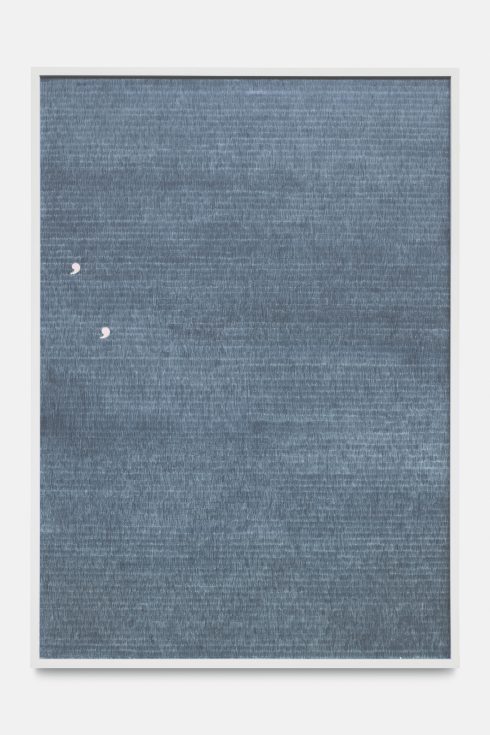

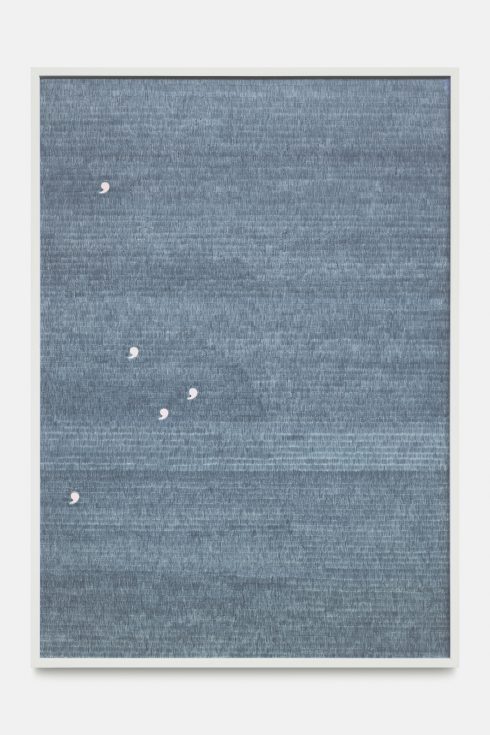

GL: From the outset, we chose to address Boetti’s fascination with mathematics and seriality, with an important body of works related to classification and numbers as well as measurement, sequences, duplication, and finally, lists and alphabets. This theme brings together three essential pieces by Boetti: first, The Thousand Longest Rivers in the World, the result of research conducted with his wife Annemarie Sauzeau from 1970 to 1973, and an enormous work of classification on an international scale published in 1977; second, Raddopiare dimezzando (1975), a performative sequence of surface-doubling by halving repetitively a single sheet of paper; and third, Lavoro Postale (37 modi di affrancare una busta) (1972), testing combinations of postal stamps and reflecting on the chain of postal transmission and its randomness. With these works we then associated Folia (1979), featuring a Fibonacci series by Arte Povera artist Mario Merz; Marcel Broodthaers’s initials on a film reel titled M.B., 24 images/seconde (1970); and a work made by Ignasi Aballi which combines squares of different colors, Traduction d’un dictionnaire japonais de combinaisons de couleurs (2018). Having identified order/disorder as an essential theme in Boetti’s work and as an overriding theme in Frederic’s collection, we decided that the first floor would then respond to the ground floor with a focus on disorder. The disorder axis is mainly addressed through the notion of assemblage or fragments that are aggregated into a whole, while its counterpart, the order axis addressed through sets of grids and intersections, or even geometric and minimal abstraction (more reminiscent of Boetti’s early work) on the second floor.

FG: Boetti was obsessed with the grid, and I’ve been collecting a lot of geometric works since the beginning. This was an opportunity to show the most minimal and historical works in the collection, such as those of Piero Manzoni from Italy and Sol LeWitt from the United States, but also to confront them with more chaotic contemporary artists, including Aline Bouvy and Jürgen Ots. Another theme that was dear to all three of us [laughs] is the role of artists in the conception and realization of a work, and in particular how they might delegate other steps of their creative process.

GL: This allowed us to bring together works that observe methodological considerations and examine concepts of process, labor, and tools. We were thinking of Boetti’s Minimo Massimo (1974) in which he imprinted a compass with a rubbing technique, or alternatively, of when in Shares (2012), Valerie Snobeck did the same but with electrical outlets. The working clothes that make up a geographical map in Jonathan Monk’s World in Workwear (2011) also take on a special meaning as they act as a tribute to Boetti’s Mappa. Other works on the same level are either produced by a mechanical or hands-on type of intervention. More works are the result of external interventions, either through natural phenomena, or developed by a third party intervening via a protocol.

FG: As an example, Tomàs Sararceno had spiders execute his work, while Gedi Sibony sliced out parts of trucks where advertisement had been erased by house painters. It was also an opportunity to present works resulting from performative processes such as those of Anne Imhof and Alice Anderson.

GL: Speaking of performative processes, time was another theme that corresponded very well with many of the works in the collection. We explored different notions of time: the “geological” time of the Earth and nature evoked by Julian Charrière’s piece, and also those of Alicja Kwade and Otobong Nkanga. The works of Sarah Sze and Lisa Oppenheim deal with more of a “stellar” type of time that we imagined in dialogue with a small painting by Boetti titled Extra Strong (Io sono un sagittario) (1992). Maria Kley or Miroslaw Bałka approach human time in its essence, while Roman Opałka approaches his lifetime through counting, just as Marc Buchy does in his performative pieces in which time lived is the primordial factor.5

FG: These last two pieces are recent productions, very much in line with the way Boetti contrasted a “productive” sense of time characteristic to his native city, Turin, with a preferred “dreaming” type of time. He also liked to “kill time”: Ammazzare il tempo, the title of a blue ballpoint drawing on paper (1983), and also of tapestries, can be read in different ways. The title is a political slogan encouraging the viewer to kill time, but, paradoxically, it can also be seen as a reference to the time spent by his assistants methodically covering all the free space with their Biros.6 I also see in it the evocation of the time that the spectator takes to decipher the encrypted message. As Boetti would have appreciated, the exhibition also owes much to chance. But chance is never entirely innocent, and even if things happen by chance, they often turn out to make sense in the end. The exhibition has thus evolved over the months of lockdown and through the many postponements, which inevitably modified its scope. Initially conceived for only a few rooms, it now extends over almost the entire building.

CJ: The encounter with the space is indeed the most decisive factor in the hang. Did the long renovation period and the delays caused by the health crisis force you to revisit a certain number of decisions concerning the hang or the flow of the exhibition?

GL: If we had initially conceived the project following a nomenclature and narrative logic strongly linked to Boetti, we did not ignore the actual space in which it would take place. As we assessed the reality of the existing rooms and those undergoing transformation, and the layout of the available walls, the project kept evolving. It was necessary to rework the visitor’s trajectory according to the number of rooms dedicated to the exhibition and circulation options. The building thus held a crucial and autonomous role in this process, with all of its potential and constraints, and its changing parameters during the refurbishing process. Therefore, it is also a question of flexibility, which was required of us all during this pandemic year. Depending on the number of accessible rooms, we had to rethink the circulation plan. Frédéric wanted to save some larger works for semi-permanent installation in the back building, where the ceiling is higher, such as for Imi Knoebel’s large diptych and Michel Parmentier’s delicate transparent paper pieces. This last work is counterbalanced, as is often the case in the exhibition, by a very small piece, in this instance by Fernanda Fragateiro, an open marble cube that creates a space of tension. The hang of each wall asks to be read like a sentence. The installation doesn’t tend to demonstrate a theme but to instead explore subtle and plural notions expressed in the works of the artists in the collection. The retinal impression resulting from the close proximity between one work to another can generate various modes of understanding and apprehension. That is at least what we attempted to create through means of juxtaposition and successive narratives. Boetti would hang his work in a particularly dense way, allowing for an expansive exploration of a single subject and resulting in impressive mural compositions such as in his Arrazi installations titled Order and Disorder (1985–1986). So, we took up his wall compositions to create what I call “clouds,” grouping sets of works in a cartographical way. This mode of presentation— close to the cabinets of curiosities that you often find in the homes of private collectors—is so characteristic of domestic arrangements and corresponds well with the choice to show art in a residential space.

CJ: Despite these successive adaptations to this evolving exhibition space, were you able to create a trajectory through these rooms that ultimately made sense? GL: Yes, you make your way through the exhibition as a sort of “Boettian wandering,” getting as close as possible to his concepts, his explorations, and deviations.

FG: We chose to start the exhibition outside, from the public space, with works open to the world: three national flags transformed into camouflage motifs by Société Réaliste, in reference to Boetti’s Mimetico (1967). They announce the color and feel of the exhibition. You will also be able to see, cast in one of the window frames, Joël Andrianomearisoa’s double-message piece, In love with the world/But I will be home soon. Upon entering the building, your attention is then drawn to two textile works related to language, therein introducing us to Boetti’s world without yet diving into specifics. With Art Is Myth I Am Real, Babi Badalov evokes the dual quality that Boetti claims for the artist, ordinary but visionary. Boetti certainly would have appreciated Gabriel Kuri’s reproduction of a cash register receipt and the pile of posters by Peter Liversidge, who shares his interest in mail art. His work, a poster that reads: “I propose that we should walk together,” encourages visitors to move around the exhibition.

GL: Lawrence Weiner’s large wall piece TAKEN APART & PUT BACK TOGETHER AGAIN (Statement cat. #805) (1997–2021), which comes with specific installation instructions that have been discussed with the artist’s studio prior to execution, resonates with the transformation of the place.

FG: And it also acts as an encouragement for the occupants to undo in order to redo, to find the best combination of elements possible. I like that its interpretation is broad and remains open-ended.

GL: After passing through the hallway, dedicated to the written and spoken word, you enter the ground floor of the rear building, moving into a room devoted to sequences and seriality. The exhibition then continues on the four upper floors. The different themes relating to order and disorder are spread out across three levels, until you reach a more minimalist-themed room. This large room on the fourth floor, Frédéric’s future living space, which links the back and front of the building, is dedicated to the idea of the artist living in the world. After a foray to the fifth floor and the theme of duality and otherness, the visit continues through the theme of process and delegation in the front rooms on the third floor. On the second floor, we continue with the theme of time and space; then we arrive on the first level to find the works of artists who capture the impalpable with a selection of what we call “World Reports,” before moving on to a more dystopian vision of the world.

CJ: Frédéric, is it really a coincidence to find in the space of your future apartment the section on “The Artist in the World”?

FG: Once again, as luck would have it. Boetti was not personally involved in the political or social struggles that were raging in Italy in the 1970s. He was in fact quite disillusioned by the way those who wanted to fight against injustice were imitating those they opposed. Instead, he sought to represent political problems in a different way, especially conflicts of state, which he symbolized with maps of war zones. His answer was travel, a certain form of exodus. I too was attracted for a long time to formal works—and to traveling—before becoming more and more interested in subjects dealing with the human or the social.

GL: In this room, we designed a wall composed of geopolitical questions. After much discussion with Frédéric, we wanted to respond to Territori occupati, one of the first maps Boetti embroidered, in 1969. On one side of the room is a large collage by Curtis Mann, a patchwork of demonstration scenes in Gaza; on the other is a piece by Israeli artist Ella Littwitz, with samples of land taken from this terra incognita, which represents all the states where Israeli passport holders are denied access.

FG: We were very much interested in cartography and territories in conflict, but considering Boetti’s openness to a diverse, multilateral world, and to non-Western cultures rather than to political action, we opted for a more open approach, that of the artist in the world.

GL: On this wall, we decided to start with two central works: Berlinde De Bruyckere’s tapestry, where she is reflecting on the outside world from under a veil, and Anne Collier’s portrait, which “captures” the world on film. Here we bring together more engaged pieces on the issue of colonialism and exile, with works by artists such as Shilpa Gupta, Kader Attia, Vincent Meessen, Margaret Courtney-Clarke, Hank Willis Thomas, Kapwani Kiwanga, Mathieu Abonnenc, and Barthélémy Toguo, among others.

FG: Berlinde De Bruyckere’s piece is particularly well matched by Luciana Magno’s video Transamazônica, in which the artist hides under her hair as a protest against Amazonian deforestation; or the video Louis-Cyprien Rials shot in Mogadishu, which shows an idyllic landscape, seemingly protected from the world’s upheavals that we gradually understand to be the site of an ongoing war.

CJ: What about the section titled “World Reports” on the first floor, what is the counterpart to this? Boetti’s Aerei, made with a ballpoint pen on paper pasted on canvas, evokes an anxious feeling, with its swarm of airplanes in a glowing sky. Photographs by Julian Charrière, Kapwani Kiwanga, and Harold Ancart surround it. Benoît Platéus’s urethane cans, and Didier Marcel’s ultramarine Labour bleu evoke a striking reminder of pollution, burnt nature, and toxicity in the soil.

GL: We wanted to end the exhibition with this group of works that show how today’s artists convey their feelings about the state of the world, like a damning report. Many of the artists in Frédéric’s collection bear witness to an uncertain world and question the state of nature, the air, the sky, the sea, of humanity and our responsibility in the face of these changes. It is a kind of condensed version of a potential project about the Anthropocene, which Nicolas Bourriaud addresses in his text.

CJ: In the projection room, a video by Christian Jankowski, which shows a specialized company cleaning Nam June Paik’s studio, raises the question of artistic heritage and the status of artistic production. How does this piece fit into the collection, and more particularly into the exhibition?

FG: Order and disorder, the figure of the artist, the delegation of work, and so on: the video touches on several subjects generally addressed in the exhibition. I wanted to acquire a work of his for a long time. When we began developing the themes of the exhibition, this video, which I had seen in New York in 2012, appeared to kill two birds with one stone. It is both representative of Christian Jankowski’s work and completely relevant to the exhibition.

CJ: Apart from a music room that includes, among others, a poetic and textual Song Machine by Athanasios Argianas, which gives a sort of visual sonority, we still have to talk about the last room, dedicated to the ‘beginning of the collection’.

GL: Indeed, I proposed to Frédéric a sort of “genesis” of his personal history with the collection, a bit like the display in his current apartment where bits and pieces of it are casually displayed all over. As described in our first interview in this publication, here we present the founding links of the collection: a hang in the spirit of Malraux’s Imaginary Museum exhibition at the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul de Vence, which Frédéric and Boetti both visited, and from artists who participated in Magiciens de la terre, which brought together Boetti’s work, a sand painting by a Navajo Native American, Richard Long, Karel Malich, and Raja Babu Sharma, which triggered Frédéric’s first purchases in 1989. We also wanted this exhibition to be a conversation with the artists in the collection who had or could have influenced Boetti, who was born in 1940: with Otto Wols, whom he discovered at seventeen; with Lucio Fontana, who was at the peak of his career when Boetti started his; with Yves Klein and Piero Manzoni, who died (the former in 1962 and the latter in 1963) as Boetti began his studies, and who influenced the young Arte Povera scene in Italy.

CJ: Among the contemporary artists in the exhibition or in the collection, are there any who have claimed Boetti’s legacy?

FG: Some of the artists in the exhibition who shared common interests may have known and appreciated each other. I’m thinking of Mel Bochner, Mario Merz, and Hanne Darboven, for example. The only one from my collection who does it in a direct and deliberate way is Jonathan Monk with his Mappa made of work clothes, but we can certainly evoke Evariste Richer whose work exhibited here not only claims Walter de Maria’s Broken Kilometer, but also reminds us of Boetti’s Legnetti colorati (Little colored sticks). Unfortunately, I don’t have any works by Mario García Torres, who clearly asserts a link with Boetti, but we talked about him and reviewed the film that we particularly appreciated at Documenta 12. Grégory and I wanted to limit the acquisitions for the exhibition, instead starting with the many previously acquired works.

CJ: So you made very few or no acquisitions in recent months to complete the exhibition?

FG: We’ve been working on the exhibition since November 2019. It was actually supposed to open, along with the building, for Art Brussels 2020, but we decided to make the best out of the subsequent delays. Before any exhibition, I become a bit of a monomaniac and my eye is drawn to pieces that are related to the exhibition themes, so of course my purchases are somewhat biased. There are about a dozen works in the exhibition that the artists created after the start of this curatorial triumvirate. Did I think about Inaspettatamente when I bought them, or was I simply pursuing broader associations? It is hard to say, because I also acquired some pieces that are not related to this project and some that I was thinking of, but that won’t be included in the end. On the other hand, I acquired three of Boetti’s works specifically for the exhibition because I had ten of them, but the artist did not like even numbers. At the last fair held in person in 2020, Grégory drew my attention to a puzzle Boetti made for an Austrian airline. I was then attracted to a sale of an original work in the Aerei series. By then I had twelve of them … but luckily Grégory found a poster of The Thousand Longest Rivers on eBay, which is important in terms of sequels and series. So there are eleven original works (Boetti’s favorite number) and two prints.

CJ: Beyond the different themes or notions addressed throughout Boetti’s work, is there a narrative, a common and unifying point of view that makes a story?

FG: I would say that the unifying element is more of a point of view or a way of seeing, and more precisely the one Boetti would hypothetically have had over my collection. Beyond the various themes articulated in the show, it is this spirit that presides over the project. I’m thinking, for example, of Fabrice Samyn’s piece, where in the first days of the exhibition a visually impaired person will create a cloud. In addition to its relevance in terms of the delegation of execution, this piece reminds us that Boetti was interested in people who possess particular gifts, especially those with perceived disabilities. Fabrice’s work consists of a braille text that only the blind can read, as well as a piece of fibrous porcelain inspired by a braille poem, which a blind visitor can read, but only the nondisabled can see. Boetti sometimes engraved on his works the words “I vedenti” (the sighted), in a kind of inverted braille. Boetti, who appreciated touch as much as sight, would certainly have appreciated a blind person’s hands-on porcelain—which I think will look like the cement spheres in the self-portrait that Harald Szeemann exhibited in the celebrated exhibition Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form. Sometimes the connection with Boetti came later, for example with this sculpture by Katinka Bock, which we liked very much but seemed a bit out of place. The title discarded all hesitation: Zucker und Salz (einfach) [Sugar and salt, (easy)]. It clearly relates the piece to Boetti’s work, as it highlights the duality between the two given elements: looking identical but tasting different. Boetti had already given this title— Sale e zucchero—in 1972, to a work made with bags of salt and sugar. We weren’t even aware of that at the time.

CJ: More anecdotally, you spoke of the taste for travel and hospitality, values shared by both Boetti and Frédéric. The notion of hospitality permeates a whole area of today’s artistic scene. Is this aspect developed in some of the works on display?

GL: We wanted to evoke the connection with traveling, the experience of living somewhere else, of center and of periphery, but also of exile and integration into a culture other than one’s own, which is connected to geopolitical circumstances. Between 1974 and 1976, Boetti traveled to Guatemala, Ethiopia, and Sudan. He was fascinated by non-Western cultures, including those of Central Asia, like Pakistan and Afghanistan, which he visited regularly until 1979. The parallel with Frédéric, who has always travelled a lot, is subtle but meaningful. The parallel operates on the notions of setting and of its utopia, and on the very Boettian notion of invitation, which coincides with the opening of the new building. Frédéric is dedicating it to the discovery of art, to coworking, and to living, since it will be both his home and that of future tenants. The One Hotel in Kabul, which Boetti created, was for him an opportunity to experiment with hospitality through the reception and invitation of others. The artist shared his projects with his guests, exploring the porous border between the role of the interlocutor and the witness invited to elaborate a process. This was part of his life, and his lifestyle was part of his practice as an artist. He took advantage of this to develop a substantive work, especially with local artisans, which was based on his awareness of their participation in the work. He made hospitality his daily activity without needing to elevate it to the level of art.

FG: You could say that One Hotel is an artistic project rooted in daily life. He was, in this case, a precursor to artists associated with the relational aesthetics described by Nicolas Bourriaud. My project could be situated, in a more subtle way than that of Boetti, but still in the same vein, since I hope to bring together contemporary artistic practices and casual visitors under the same roof in the hope of generating fruitful results.

GL: This reminds me of Allen Ruppersberg when he built Al’s Grand Hotel in Los Angeles, in 1968, an art project coupled with a seven-room hotel to welcome the public for three months. In addition to welcoming visitors, he wanted to share with them his personal imaginary by inviting them to participate in his artistic project. But this host-to-guest relationship is sensitive. It is a question of setting appropriate boundaries, of negotiating and defining each other’s space, of generosity, and of awareness of one’s own position.

FG: The occupants of the building, coworkers or tenants, will not necessarily be contemporary art lovers. I didn’t want to create an art foundation for the art world’s insiders, but a place that would allow everyone to live and work among works of art. A place that can stimulate and challenge them in new ways, in their daily life on a long-term basis. I also intend to organize exhibitions around the collection, meetings with artists, conferences, and such, hoping to attract a mixed audience with different types of art lovers, and in this sense, to try and create a cross pollination of participants. The idea is to create a bridge between art and everyday life, something Boetti practiced with great skill and dexterity throughout his own life. I hope that the creativity that inspired and guided us in the curating of Inaspettatamente will remain within these walls well beyond this exhibition, and give a new dimension of time and space to this building.