Inaspettatamente

Dirk Snauwaert

What would Alighiero e Boetti have made of this pandemic crisis, we wonder? He who never let a crisis go to waste, using them as a source of inspiration for his art and his way of living. Inaspettatamente: as if in the actual blink of an eye one suddenly becomes aware of the neural transmission between the brain and the retina. This momentum, and the appreciation of speed and immediacy that we gain from it, became inaccessible to most of us in the last year, as the world unexpectedly came to a halt. The anticipation that grew as we await(ed) the end of the crisis is/was palpable, creating an atmosphere of suspended time until the social restrictions lifted, and life returns in its full, vital force.

This lack of human interaction and exchange had only one channel of compensation: cyber telecommunication networks. However, these virtual alternatives and digital information highways only allow for an impoverished version of visual perception and sensation, through reduced and compressed sets of synthetic data and signals.

Boetti spent a lifetime investigating the relation between signal, meaning, and action. He obsessed over the habits and conventions of humankind: its presumptions and its compulsive behavioral patterns that oscillate between generalized animosity and refined states of play. He probably would have embraced the crisis and its ambient instability to create rebuses and puzzles from the pervasive images, signs, and signals that flooded our screens. He would have questioned the standardization, conformity, and uniformity that increasingly characterizes these symbols, thereby drawing our attention to the very nature of how we perceive and assign meaning.

One of Boetti’s main concerns was how the mass media instrumentalizes form to control collective behavior and reinforce existing norms. The strange parallel that has arisen during the pandemic between people’s general inaction on the one hand and the unprecedented abundance of digital content on the other would have likely amused him.

The slowness that Boetti espouses however lives in stark contrast to the contemplation and cognitive distance imposed by the crisis. He preferred a fully engaged, hands-on approach to these matters, actively finding new ways of disrupting and altering the patterns of repetition that strengthen the unstoppable current of mass production and consumption. In this way, he sought to deregulate the automatisms with which codes trigger behavioral patterns via standardized communication. The aim was to restore the natural ambiguity, slippage, and spontaneity of language, as well as our freedom to create meaning.

Slow, precise perception rather than speed and efficiency usually distinguishes the approach of private art spaces from public institutions, where visitor numbers have become a proof of legitimacy and a prerequisite for funding. Several initiatives of worldwide private collectors, however, prove that appreciation and careful perception can still prevail over excessively showcased “trophy” or fetish artworks. The latter form of art and its associated superficial context is closer to that of luxury commodities, overvalued by both the media and the ticket office.

In choosing the site and flagging the unexpected in the title—a direct reference to Boetti’s work—Frédéric de Goldschmidt moves away from the exhibition blueprint currently circulating in the arts and cultural management sector, one that often relies on brand strategies and extractivism.

We can see in his collection that de Goldschmidt chose to take the longer and riskier path of selecting and composing a wide-ranging spectrum of contemporary works. Spanning several decades, his choices are eclectic without being encyclopedic or arbitrary. It demonstrates a sensitivity to the careful negotiation that must take place between artist, artwork, and receiver, with a preference for poetic, self-aware, unspectacular, and formally complex constructions rather than pop icons or commodity-driven art and graphics.

Boetti’s careful deregulation of the lines of communication and their fast-flowing signals stands in direct contrast to the name and location of the space: Quai du Commerce. If trade and commerce are ostensibly taboo in the world of private collectors (because taste and non-conformity reign supreme), then the name draws attention to this ongoing tension.

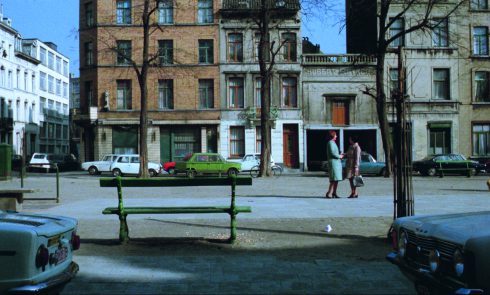

The modest piers and docks of Brussels’s historic harbor, which live on as street names, have exactly the opposite vibe of the new Parisian art space, Bourse du Commerce, where luxury, exclusivity, fast circulation, and sensationalism prevail. The Brussels space contains echoes of the slowness of the barges and canal boats, of farming, and the shifting seasons and harvests, while its French counterpart recalls more the world of high-frequency trading and finance. Visitors to the Quai du Commerce will stroll along the facades, shop windows, and boardwalks to get to Frédéric’s art space, where afterimages, visual echoes, and latent memories are reminiscent an address down the street.

23 Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles, the subtitle of Chantal Akerman’s illustrious film Jeanne Dielman, continues to influence our modes of perception and interpretation even today. In gradually becoming aware of the second nature of the compulsive, repetitive, and normative gestures we perform every day, the film’s lead Delphine Seyrig keeps pushing our minds to new heights of understanding. Her daily routine consists of leaving her quaint apartment to take a walk in the neighborhood, specifically around the Quai du Commerce. She slowly realizes that escaping her monotonous life would be possible if she could only disrupt the cycle of traditions and reproductions that have regulated her life and sexuality.

The film and its decor have been both heavily criticized and praised for their banality, mediocrity, and lack of fantasy. The mechanical and repetitive tasks that make up her daily routine are the most defining element in the film’s aesthetic, captured by the camera work of Babette Mangolte as incredible frontal picture-window images.

Repetition amplifies the experience of duration and time. In focusing on the passing of time and slowness, Akerman goes against modernity’s cult of speed and our addiction to overcoming space and temporal constraints to show us, via a three-hour viewing experience, how we might overcome conventions and break out of the unquestioned patterns that govern our lives.

Since Inaspettatamente coincides with the end of confinement and self-isolation, let it also carry the memory of the lockdown’s duration and motivate us to reflect on temporality and age. If our generation is compelled to add a new category to the existing symbolic models of time—cosmic, geological, and biological—this new category will need to take global warming and climatic time into account.

Many artworks in Frédéric de Goldschmidt’s collection reflect an awareness of time, of its actual duration, without being fatalistic about the inevitable end. The coincidental correlation between the building, the street name, and Chantal Akerman’s film, brings together abundant material and impulse for a new genre of art center that can overcome the routines, logic, and spectacles of the expected.