Collecting Experiences and Experiencing a Collection

A conversation between collector Frédéric de Goldschmidt and curator Gregory Lang

GL: Frédéric, we are currently in the building you are renovating to house your collection on a permanent basis, and to finalize a selection of your works in dialogue with Alighiero Boetti for Inaspettatamente, the inaugural exhibition we are curating together.

FG: We’ve known each other for ten years and most of it has been around art. I’ve seen you grow and evolve as a collector, but I still don’t know how it began.

Let’s begin by discussing your first influences. What were they and how have they shaped your collection?

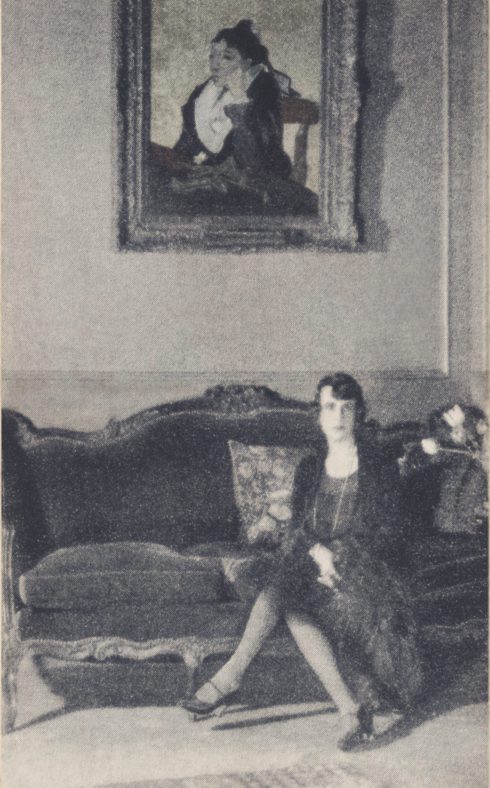

FG: My first art moments were with my grandmother, Marianne de Goldschmidt-Rothschild. She was quite a personality. She liked to tell the story that when she bought Van Gogh’s L’Arlésienne1 at the age of twenty-two, she had to hide it behind the curtains in her room when her father visited. When we regularly had lunch, “Madame Ginoux” was hanging in the dining room of her Paris townhouse, a Manet was hanging over the living room’s fireplace, and there were a number of Impressionist paintings and drawings in other rooms.

When I was twelve or thirteen she took me on a daytrip to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, to see Rembrandt’s Night Watch. This was very extravagant at that time, but she really wanted to share her passion for art with me.

And it worked! When my father, Gilbert de Goldschmidt2, started a collection of postwar abstract art, we often looked at artworks and discussed them together. Sometimes he asked for my advice before making an acquisition. He bought great works from artists such as Nicolas de Staël, Zao Wou-Ki, and Hans Hartung.

Art connected us. I was happy to receive a few presents over the years. The first piece he gave me was an etching by Hartung. I also received a lithograph by Zao Wou Ki and one by Roberto Matta.

GL: Could we then consider these three works from your father as the origin of your collection?

FG: Yes, they were definitely the first artworks that I owned and hung in my bedroom. At that time, I mostly collected postcards from museum exhibitions and displayed them in my bathroom, along with an African statuette that I brought back from a holiday in Côte d’Ivoire.

GL: I love that it started with postcards. It shows that you were already collecting memories at an early age. Is there one exhibition that you specifically remember?

FG: In the summer of 1973, my father took me to Saint-Paul de Vence, to Fondation Maeght to see an exhibition that was a homage to André Malraux. It was an eclectic mix that reflected different moments of his life—from Khmer statues to Picassos.

GL: Lucky you! What an iconic exhibition! I only know it through the catalogue. What still sticks in your mind from the show?

FG: I actually remember the beautiful surroundings better than the works.

But as a postcard collector, I was impressed by the variety of pieces from different times and origins. The artworks “spoke to each other” and “spoke with me,” even though I did not know anything about them. This show gave the artworks the opportunity to be in dialogue based on Malraux’s personality and taste. The curatorial choices were quite unorthodox. It was a big departure from what I had seen before in a museum.

Malraux thought all objects should be on the same level, even if they were each created for different purposes, for example the stained glass window of a cathedral, Vermeer’s Milkmaid, an African fetish, or a painting by Chagall.

As a private collector today, I am very much on the same page, and the show made me realize that sometimes the environment and curating matter as much as the artworks themselves.

Malraux made a prescient observation when he coined the concept of the “imaginary museum,” where any object, profane or sacred, can be part of one’s personal and mobile museum as long as it inspires imagination.

I have felt this myself. When I bring home a new work, I enjoy how it connects with the ones already there, especially in the way they interact and activate each other.

GL: Today, in your apartment, you have ethnographic objects coexisting with artworks from recent times. You are indeed in the lineage of Malraux’s Imaginary Museum: a Zulu hat next to a work by John Baldessari, a New Guinean currency near a print by Francesco Tropa, a Cambodian bell next to a jug filled with urethane by Benoit Platéus. And above these, you have camouflage flags hanging from your ceiling that erase national symbols. How does this shed insight about who you are as a person and as a collector?

FG: I live in a seventeenth-century house in the center of Brussels. It is an attic loft with a lot of character. I have filled with objects from different moments of my life and from different periods throughout history.

One side of the apartment overlooks a former canal, which was once part of a bustling commercial port for the city. In contrast, on the other side is a much more modern building.

As an example, on one side of my desk hangs a piece from 1967 by Patrick Saytour, which is made with a burned oilcloth; and on the other side, a piece by Bertrand Lavier from 1987 juxtaposes a tennis net on a volleyball net.

As in the way I kept the large wooden beams of the ceiling with marks left by the craftsmen intact, these works are embedded with the same sense of rawness I appreciate. I think they are reflective of my approach to both life and to art.

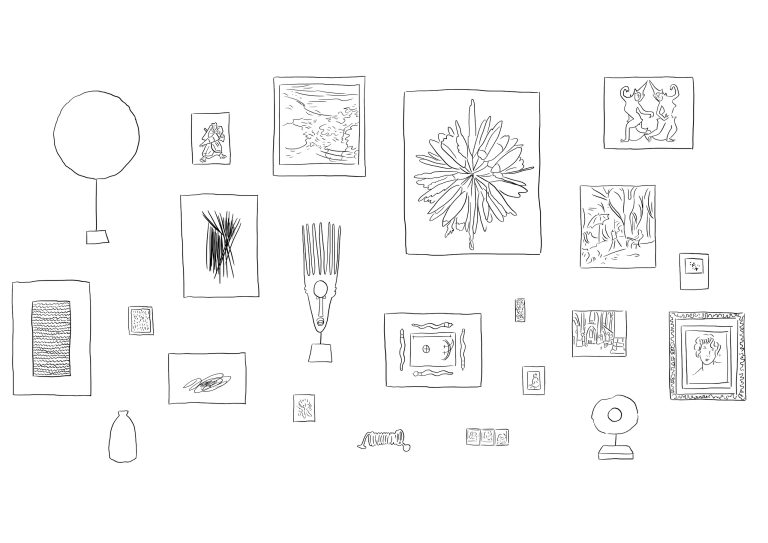

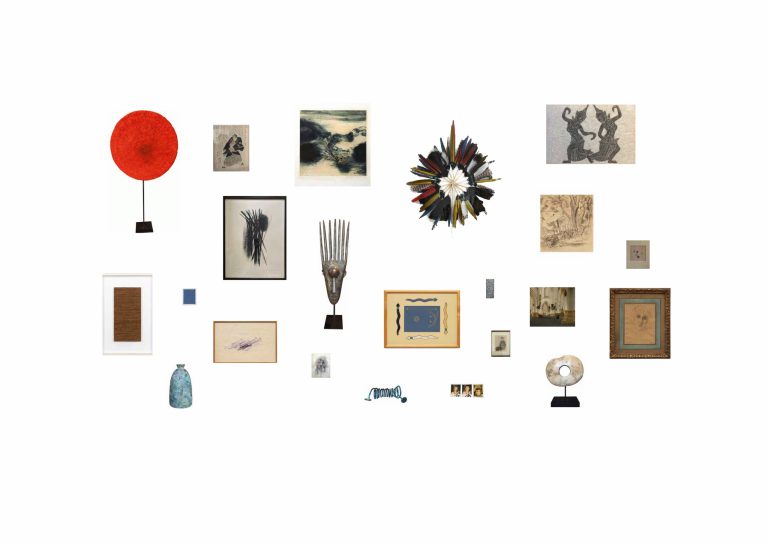

GL: I think that it is important that we create a room within the show that captures this atmosphere.

FG: That’s a good idea indeed. It would be nice to provide a context that is more personal, even if it is not totally related to the exhibition’s theme.

GL: So, in order to conceive this room, we should address the events that made you into the collector you are today. Is there any specific moment that left a memorable impact on you?

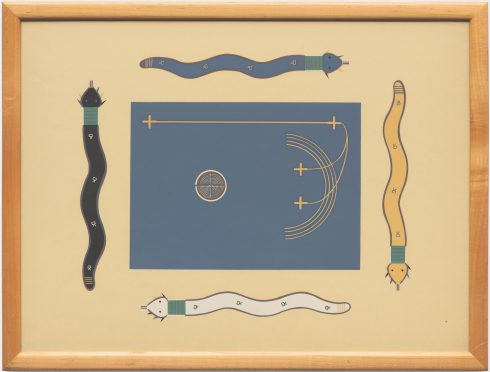

FG: In 1973, a few months after the Malraux show, my grandmother passed away. Before she died, she had given to me a portfolio she had brought back from her exile in America during the war. It was made by an artist who had transcribed sand paintings by a Navajo “medicine man” onto paper, which illustrated ancestral stories regarding the origin of the world.

I loved them so much that I framed the series and hung them in my first apartment. I certainly did not know at the time the impact it would have on my future endeavors. As I really wanted to see an actual sand painting, I went to see an exhibition whereupon a Navajo artist had traveled from America to France to make a sand painting in situ. The show, Magiciens de la terre, took place in 1989 at Centre Pompidou and the Grande Halle de La Villette in Paris.

It was in this exhibition that I discovered the amazing embroideries made by Afghan women for Alighiero Boetti, and this triggered my first acquisitions of contemporary art.

GL: I want to know more about it! The show went beyond the established Western point of view and connected contemporary art with the non-European cultures that attracted you. What do you remember of it?

FG: At the time, I couldn’t foresee its importance. I was just attracted to an exhibition that encompassed artists from all over the world. What I particularly remember are the works by African artists, such as Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. I was also fascinated by the Ndebele huts, and enjoyed stone sculptures from a Zimbabwean artist.

It definitely encouraged me to acquire works by living artists unknown to most people. My first attempt was to buy a work from that Zimbabwean sculptor, but it did not work out. Mind you, this was in 1989, so getting in contact or arranging shipping wasn’t as easy as today.

I don’t know why I had not bought from art galleries before. Maybe I wanted a challenge. Or I just thought these works would be more affordable.

I was particularly drawn by small Tantric drawings by Raja Babu Sharma, an artist from India. I did some research and finally found him through the Jaipur Tourism Office, I think. I wired some money and a few weeks later, I received three drawings in the mail. I was very excited when they arrived. I had no idea when they would come, or what they would look like. Somehow, this was the first purchase I made without seeing the work.

The other artist who struck my mind was Karel Malich, from Czechoslovakia. Many of his pastels were exhibited in Magiciens de la terre. I had always liked this medium, with the combination of softness yet brightness the colorful crayons give to the works. The artist was sixty-five years old and living in Prague, so I chose this destination not only because it was a romantic hideaway to propose to my future wife, but also with the hope of meeting with the artist. And through a Czech friend, we finally got an appointment and visited his studio.

I bought two large pastels very similar to those from the exhibition. I kept them on my walls for many years until I decided to replace them with more recent acquisitions. These were probably the first significant works I acquired with my own money, but still without consciously starting a collection.

GL: So, it was Magiciens de la terre that really triggered you to buy art! We could mix works by artists who participated in this amazing exhibition with the spirit of Malraux’s Imaginary Museum as a starting point and to encapsulate in this room the first works and artists you encountered. So, can we consider Karel Malich to be the first among many future studio visits?

FG: Actually, it began sooner. It was when my father brought me with him to visit Henri Pfeiffer, a German artist who had taught color at the Bauhaus in the late 1920s. My father was very fond of his work and bought several pieces from him that we chose from stacks in the artist’s garage in the suburbs of Paris. In fact, the artist gave me a small work as a present. I’ll show it to you if you want to consider including it in the show.

And before that, as a kid, I was visiting my grandmother’s studio at her house in the South of France—my favorite place on Earth. Indeed, she was an amateur painter, who went by the pseudonym Marianne Gilbert.

GL: Do you still have works of hers? If so, we should include them in this room.

FG: I have one. I will be happy and proud to have her in our show. And It makes me think of another story that involves my mother and an artist I met!

When I was in my early twenties, I worked in New York. It was a very dynamic time to be there. I saw the works that Keith Haring was doing in subway stations. I wish I had bought works by New York artists at the time but, unfortunately, my only acquisition from those years was Haring’s “Pink Book.” A limited edition, not an original …

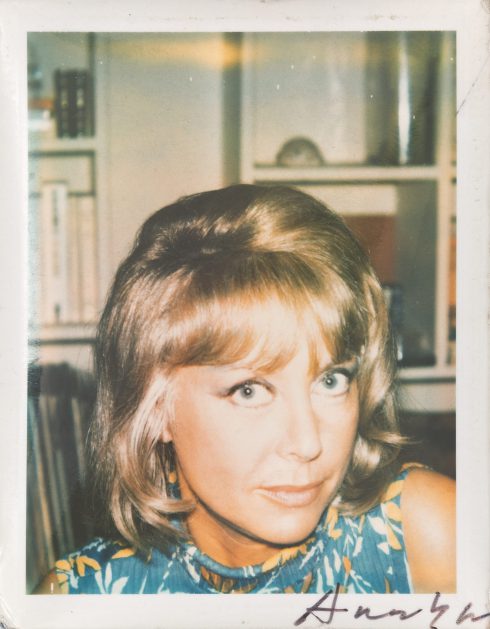

I also met with Andy Warhol a couple of times, but it wasn’t until much later that I bought a few of his works. And imagine my surprise when at the age of ninety, my mother3 told me that she had been photographed twice while he was in Paris. She did not like the photos, but I will show them to you.

GL: Thank you for sharing these amazing stories. I can better envision this room now. However, when was it that you “officially” started collecting? Tell me about the first acquisitions you made at a gallery or an art fair?

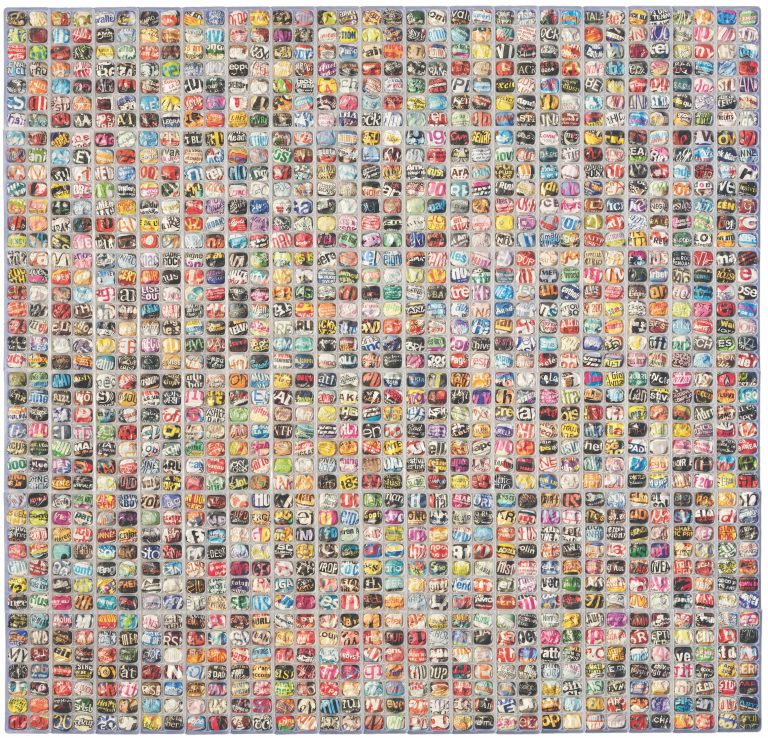

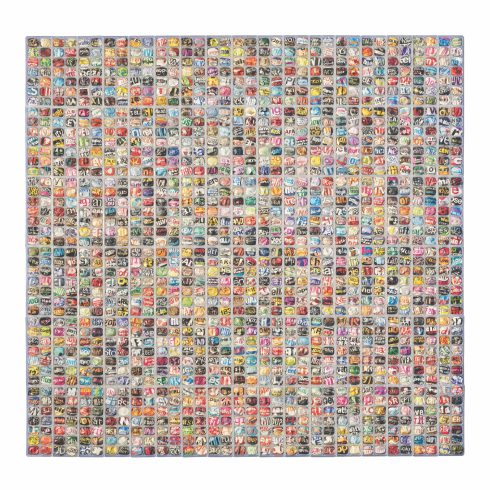

FG: Like a lot of Parisians, I was going to FIAC every year as a weekend outing. In 2006, I went to the Grand Palais during the last hours of the fair and I was struck by a series of works made with ice-cube trays filled with crumpled magazine pages. It was by a young French artist, Benjamin Sabatier. Although everything was sold out, the gallerist, Jérôme de Noirmont, told me he would have a show by the same artist the following May. So, I went to the gallery at the beginning of the vernissage to make sure I didn’t miss out this time. And on that day, I finally bought an artwork from the series I had seen at FIAC.

GL: That’s an unexpected choice. Why this particular work?

FG: The fascinating thing about this work was that even though the magazine pages had been ripped up and wrinkled, he somehow encapsulated the essence of the magazine. I was delighted by the way he had transformed these utterly banal elements to create something so original.

That was a seminal acquisition, as it was the first time since Magiciens de la terre, almost twenty years before, that I had gone out of my way to pursue an artwork. It was also the first work made with unconventional, poor materials that would later become emblematic of my collection.

GL: So, what was the next piece you bought?

FG: It wasn’t until two years later that I actually made my next acquisition, mainly due to a lack of time and available funds. But in her will, my grandmother had left me one of her most important paintings, a portrait by Manet of a young boy with a dog, which hung above her fireplace. My father suggested I keep it safe until I could do something meaningful with it.

It thus stayed in a bank vault, except for a show in Paris and New York in 1983. In 2008, I had completed a professional cycle of my life, so I decided to sell the painting, and “recycle” its proceeds into more affordable artworks. This provided me with the means to start my own collection and follow my grandmother’s example.

I also wanted to be reflective of my time and to familiarize myself with art today rather than art from the past. I thus decided to take a year off to visit exhibitions, biennials, auctions, and art fairs.

GL: Was there a method to your pursuit?

FG: I started a collection almost from scratch and with the intention to build something, but I did not yet know what or how. Since I had not studied art, I essentially followed my instincts. The first work I bought was a sculpture by Bernar Venet, an artist I had appreciated for a long time.

I had been to exhibitions in museums or galleries on a regular basis but without the intention of buying. Therefore, before I actively began and in pursuit of acquisitions, I needed to expand my knowledge of artists and genres. Art fairs were for me the ideal places to see a large selection of works from around the world all under one roof.

My first art trip was to London, for Frieze 2008, where my first and only acquisition was a cumbersome installation made with light and metal by a young Israeli artist, Haim Elmoznino. Unfortunately, he disappeared from the art scene shortly after. On the opposite spectrum of notoriety, after visiting Anish Kapoor’s studio, I bought a golden disc! As you can see, I responded to what I saw without any preconceptions.

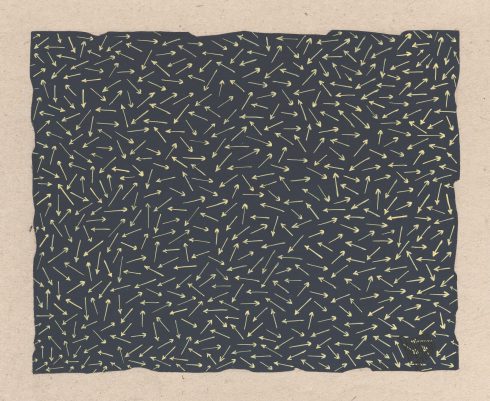

Two weeks later, at FIAC in Paris, I bought a lamp made with barbed wire and sea salt by another Israeli artist, Sigalit Landau, whom I did not know at the time. From the outset, I was willing to take a gamble on young or emerging artists, but I also wanted to seek familiarity around more established names I already knew. Thus, I was very happy when I turned around a corner at the fair and bumped into a piece by Alighiero Boetti. Although he was not a household name, the fact that he was in Magiciens de la terre was enough for me to make a decision. I loved this work of his, Ammazzare il tempo, a triptych of the series made with ballpoint pen (biro in Italian), where you have to align the white commas on the sheets with the alphabet on the side in order to decipher the title.

A few weeks later, I bought a Memory Ware by Mike Kelley, made out of white buttons, because I had seen the show he had at WIELS a few years before and particularly appreciated this series. I was not really aware of his importance but was willing to pay the price as long as I loved the work.

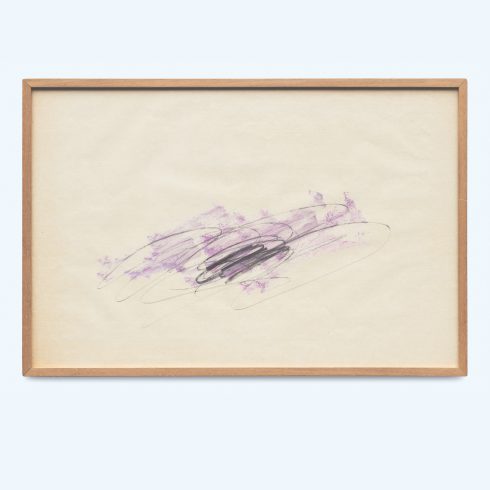

That’s also when I started to follow auctions, and I went to New York for November’s auction week. I bought a large work on paper by Cy Twombly, an artist who I had admired for a long time; a small delicate work by Mark Tobey, an artist whom I did not know—but, coincidentally, the work was made the year of my birth; and a sculpture by Roni Horn, a stick with text that intrigued me. A few weeks later, I found at an auction in Paris a series of drawings by Jean Fautrier, an artist whom my father had collected.

GL: Although it doesn’t seem at this point you had found a direction, I am intrigued by how you’ve mixed your experiences of the past with the new knowledge about art you were acquiring.

FG: It’s striking that without knowing it, you bought a work by Boetti and works by Fautrier at the same time. I read in a text by Annemarie Sauzeau Boetti, his wife, that while he was in Paris between 1962 to 1964, Boetti was fascinated by “the abstract Lyricism of de Stael, the matter of Dubuffet, Wols and Fautrier, and the Zen calligraphy painting of Japan.”4

This is even more uncanny, as my father had works by Nicolas de Staël and Wols. And he learned late in his life that Wols, a refugee in Paris from Germany just before the war, had been employed by my grandmother to help my father with his schoolwork. And I love Japanese calligraphy!

GL: Boetti would have appreciated these coincidences. It also confirms our initial intuition that Boetti was the right choice to guide us through our exhibition5.You also collected Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni, two important artistic figures in Italy that were at the height of their careers when Boetti began. How did you begin collecting this period?

FG: During the same trip I made to New York for auction week in 2008, I visited Boetti’s gallerist Gian Enzo Sperone and saw an exhibition on the Zero Group6. It was a revelation in many ways. I was simply taken aback by the works I saw.

I had never heard of these artists, but I was instinctively taken by their aesthetics, particularly the way they played with materials and light—and how they brought some non-art into art.

I realized later that it allowed me to understand better where I had been and where I could go next. Getting to know the work of this group gave a more solid context, shed new light on what I had collected, and also provided me with a vocabulary and a direction to move forward with my collection. It was really a pivotal moment.

My first acquisitions were a painting by Heinz Mack and a piece by Jan Henderikse, made with corks, both from 1960. And a work by Jan Schoonhoven made of corrugated cardboard from 1970.

GL: That was a significant step forward! I especially appreciate this historical part of your collection, and I remember that we spent time figuring out how to best hang the works on one single wall of the apartment you had in Paris. And I thank you again for giving me the chance to show these works in the exhibition I co-curated at FRAC in Dunkirk7.

Can you explain what appealed to you and how you connected these pieces with those of younger contemporary artists?

FG: The Zero Group artists transformed simple elements in novel ways and sublimated materials that many others tended to neglect. Subsequently, I collected several contemporary artists who take a similar approach. Through them, I realize that I appreciate simple gestures and subtle transformations that draw our attention to things we had not been able to see before. As Paul Klee said, “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.”

GL: The name the Zero Group ascribed to themselves was in reference to the countdown before a rocket launch. Can we say that is the Zero Group that boosted your drive to collect?

FG: Absolutely! For the Zero Group artists, it was a new beginning where the old turns into the new. Fifty years after them and under their influence, I made a jump myself with the painting by Manet and turned it into a collection of works by artists closer to my time. Coincidentally, my grandmother collected artists that were active fifty years before her and I was repeating the same pattern.

I then started looking quite actively for works by artists of that sensibility and period, like Manzoni and Fontana. I searched actively for works offered at auction. I found in Paris the edition Yves Klein made in 1966 for his exhibition in Krefeld, another Mack in Vienna, a Günther Uecker in Cologne, and a Schoonhoven in Amsterdam.

I became much more engaged and involved in the process. As such, I was following auctions, checking past results, traveling to specialized art dealers, and comparing quality and prices. In a word, I was becoming more professional. It was through this dedication that I was able to acquire these works before they became a sought-after commodity in the market.

With this research, my process evolved. As an example, I knew that I needed a piece by Otto Piene. Without a piece of his, the Zero Group artists that I was assembling would not be complete. As such, this was intentional. But there were times when I had a specific work in mind and ended up with a completely different one. And every acquisition opens new potential directions.

GL: So, then the process is organic. I would say that the collection evolved just like bamboo rhizomes: a horizontal root growing in various directions, separating into smaller subparts, and occasionally stemming upwards. Deleuze and Guattari speak of rhizomes as a type of organizational structure that develops in a noncausal and nonchronological way8. It rather operates on principles of multiplicity and heterogeneity. This type of system seems to mirror as much the way you collect art as your way of life. Art is an inseparable part of you and your never-ending search for new works and personal experiences.

FG: Indeed, the art world I discovered was a network that consisted of fairs, biennials, and exhibitions, which I realized were very much interconnected. Although many of the players and works were often similar, each event has its own unique flavor that broadened my perspectives.

You know this better than anybody else, as this is how we got to know each other. We met in several cities over the course of a few weeks. We saw the best exhibitions and attended the most obscure events. We stayed in the most luxurious suites in Milan to the most basic dormitory on a highway in Kassel where we had to share a bathroom with the other occupants, mostly truck drivers [laughs]. This was because we wanted to see and experience as much as we could.

I don’t need to remind you of the excitement we had in fitting as many pavilions, cocktails, and dinners as possible into the opening days of the Venice Biennale. In many ways, through our ongoing dialogue you opened me to other ways of seeing, discussing, and sharing art and its context.

GL: I have fond memories of all those moments with you. You certainly acclimated yourself to the art world very well. You even went a step beyond when you began mounting exhibitions of your own. What led you to do so?

FG: At FIAC 2009, I bought a work by Daniel Lergon that was too large to hang in my home. I was fully aware that it was, but I got it anyway. I would say that’s when I considered myself a true collector.

It was then I converted a space I had around the corner from my apartment to store and display my new acquisitions. I had been to some collectors’ homes during art fairs and thought I could do the same for the next edition of Art Brussels in 2010. So, I did. I tried to find a thread between recent acquisitions and came up with a title that I thought was fitting. I called it Shapes, Shades and Shadows9, as I thought it conveyed the simple forms, colors, and the movement of light within those works. Although I hadn’t meant for this to be an exhibition space, that is what it became. And from that point, collecting and showing took place simultaneously.

I very much enjoyed the process of putting this first show together. I found the entire experience so much fun that I immediately began thinking of the next show I would do. I knew I wasn’t only collecting for my own enjoyment but also to share with others. It introduced a fun, new element to collecting. I looked forward to receiving works I had bought and seeing them again.

GL: Since then, you’ve organized several shows of your collection in that small space and invited a number of emerging and international artists and curators to participate, and you have provided them exposure to collectors and other professionals in the art world.

FG: Yes, but it was not enough.

GL: What do you mean?

FG: I was frustrated with hanging and showing my works only for the exhibitions I was organizing during Art Brussels. My collection had outgrown that space and I had to rent storage. I was rotating the works in my apartment every year or two, but it was a pity not to be able to live with more of the works I felt compelled to buy.

GL: And so you acquired a larger building nearby. What were your motivations? To have more space to mount exhibitions? To show more of your collection?

FG: Both. And a mix of chance and desire as factors, too. As I was walking in the neighborhood, I went inside a building that was to be sold at auction. It had a lot of character. There was an empty screening room with no projector or seats. As a film producer, it was particularly intriguing to me. I was lucky to get it. I decided to buy the building because I saw plenty of possibilities.

I got the keys a few days later. And with the help of a young curator, Agata Jastrząbek—and a good support team—we put together a show that made the best out of this former mental health clinic. The works made out of everyday materials fit perfectly with the relics left by the previous occupants. We used three floors in the front and one in the back. I was not only able to show eighty-five works from my collection, but to also commission a few—particularly, Do not lie to me by Loup Sarion, directly inspired by the building.

As I was still reflecting how to make the best of the place, I hosted two exhibitions with local art schools11. They used the space freely and it gave me the time to come up with a concept mixing living spaces, storage, exhibition rooms, and offices.

GL: This was a big step indeed. Now that the renovation is almost complete, can you tell me more on how you’ll display the works and who you hope to attract?

FG: It will be the permanent home for my collection, but it will also be a space for others to work, live, and experience art. There are actually two buildings that are interconnected. The original nineteenth-century building faces the street and an extension was built in the back one hundred years later.

The three floors of this building will be dedicated entirely to art: I will rotate works from my collection and organize exhibitions. But there will also be artworks in the first three floors of the original building that will be dedicated to co-working spaces.

All visitors to the collection or the offices will be welcomed with a statement by Lawrence Weiner: Taken apart & put back together again. It can be interpreted in the context of the extensive renovation and reminds us about what is temporary and also the action of gathering things and people together. This is what I like in contemporary art: everyone can read something different, but it is inspiring to all.

It will be a way to turn a collection that began with personal reasons into an instrument that I hope will benefit many others. What I want to achieve with this project is to share the emotions the artists gave me with others, especially those who may not frequently go to museums or galleries. I want my collection to inspire others and enable them to be more creative in their thinking. I feel this is my responsibility as a collector, to share.

The building is going to be called Cloud Seven. Seven, as in the street number, and Cloud to connect dreaming with technology. But it comes mostly from the expression “to be on cloud nine,” or in French, “être au septième ciel,” to be in a state of bliss. It is the art that will give the building and the technology its spirit. I want our users to feel good in mind and body. For example, there will be a gym and a steam bath in the basement with a fountain in the shape of a toilet that Laure Prouvost made for the last Venice Biennale.

GL: So you mean art will literally be part of daily life?

FG: Yes! And they will also be able to stay the night. On the top floor, there will be two lofts for guests, tourists, or business visitors interested in the collection or the facilities downstairs. They will all be able to live and work in the premises of an art collection, just like me, as I will live there too.

We will also have a fun mix of events ranging from exhibitions and performances to lectures and more intimate events to allow visitors to mingle and socialize. I will also be able to welcome the general public to my collection in a more open way.

GL: I’m curious: will your occupants also be able to ‘‘curate” their own working spaces with art from your collection?

FG: Those who come to Cloud Seven can choose where they sit depending on their mood and how they feel on any given day. They will also be able to go in exhibition rooms purely devoted to the collection to reflect and relax in quieter surroundings.

Members on the third floor will be able to select some of the works they want on their walls.

GL: I also know you’ve commissioned artists to make site-specific works for the building. Tell me more about your intention and the integration process?

FG: I am indeed commissioning works from artists with whom I already have long-term friendships. One piece by Gregor Hildebrandt will recall the building’s past. I found stacks of 78 rpm records in the attic when we knocked down a partition during the renovation. I sent them to Gregor so that he would incorporate these remains from the past to make a work for the future. In doing so, I hope to connect the former function of the old screening room with that of the fully equipped multimedia room we are building.

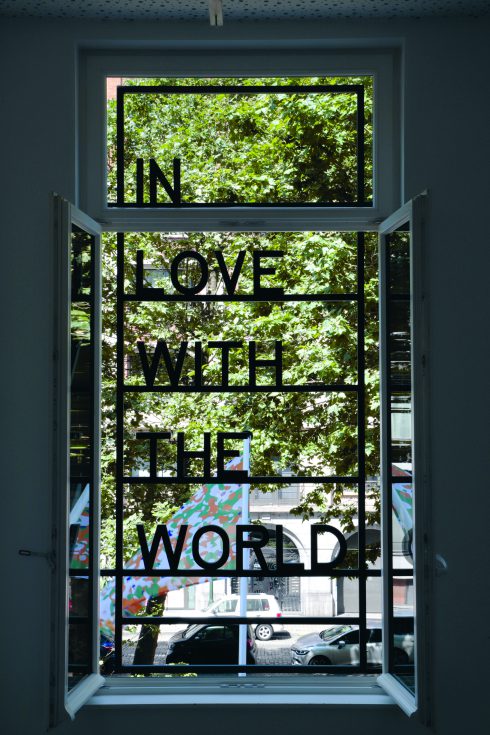

A work by Joël Andrianomearisoa will be seen both from the exterior and the interior of the building. Coworkers and visitors, but also passersby, will be able to read two sentences in cast-iron letters on two of the building’s windows: In love with the world on one, But I will be home soon on the other.

The words are there to reflect my intentions for Cloud Seven and to provide a comfortable living and working environment. It is also meant to remind us of the dual nature of the building itself, which promotes creativity and positivity within and beyond the perimeter of the building.

Nadia Guerroui will place a glass sculpture on the terrace that reflects the clouds and city to elicit different experiences that depend on the changing light and mood of the viewer.

GL: That’s really nice to create a contemplative installation, which inspires a moment of breath and personal reflection. Nadia’s piece will draw the city inside the building, especially as you are in such a vibrant neighborhood in the center of Brussels.

FG: Yes, I love Brussels and especially the art spaces that are here. It started in the late 1980s with Greta Meert’s gallery and Argos. Other galleries like dépendance and Waldburger Wouters, and institutions like Centrale for Contemporary Arts, iMAL, and MiMA came later. In a few years we Kanal Centre Pompidou will open just around the corner. I could not create Cloud Seven anywhere else than in Brussels. This is a great place for the arts, as all members of the community share their practices across lines unlike any other city I’ve seen.

GL: As you’re contributing to the Brussels contemporary art scene with this project, my question is, what do you anticipate for the future once the building is open. And how might it affect your plans both personally and as a collector?

FG: My focus is solely on this building right now. It’s a whole new chapter I’m really looking forward to opening. In addition to having the space to show a large part of my collection, I am excited to share it with others on a more permanent basis. There are still many ideas, but they will involve the community that will live and work there.

You know, one of my heroes among the Belgian collectors is the late Herman Daled. I think he collected the best work of Conceptual Art; it was extremely bold. What he did was also particularly generous, as it was mostly done to support the artists than to live with the works. He stopped collecting altogether when he felt out of sync with the trends of the art world and committed all of his time to nurturing the local art scene.

But unlike Herman, who kept his acquisitions in crates, I’m not interested in collecting just to collect. I want my collection to constantly interact and engage with new people and their ideas. I find the collaborative process really invigorating, just like the way we’ve been working together on this upcoming exhibition. And I’m sure having this space to exchange ideas with others will lead me down new paths. I’m looking forward to it.

GL: With the opening of this building, I am certain that it will open even more doors, so to speak.

FG: Yes, that’s my intention. I’m looking forward to sharing my works and experiences through this new space and beyond, but I don’t want this to be a memorial.

No matter what the future will say about these times and my choices, I enjoyed my process and hope that, when their turn comes, my daughters will also do something in line with their own times and interests.

GL: And with that, we have come full circle by connecting your grandmother to your daughters. Through your personal way of collecting art, you can empower them to find their own vision, and by sharing your collection you will inspire others just as you have inspired yourself.

FG: Thank you for sharing your personal history and insights so openly. It has been such an inspiring experience to create this exhibition with you in dialogue with Boetti and your new building.

To be continued …