(Not) All Is Gold

(Not) All Is Gold investigates the notion of value in art, whether it be at a direct and intrinsic level or a metaphorical one. Alongside works that embrace/subvert the very nature of their constitutive elements, others subtly comment on the economy of the art world and, more specifically, on the status of the artists and their strategies to survive. A special focus will also be made on works that integrate transactional mechanisms into their own creative process.

Curated by Emmanuel Lambion, Bn PROJECTS in dialogue with Frédéric de Goldschmidt.

The exhibition is built around a selection of works from the collection of Frédéric de Goldschmidt, while also making room for invited contributions (16 / 52), which have led to new additions to the collection, specific commissions, or works on loan or owned by the artists or the curator.

In addition to the selection of works by 52 artists in the main exhibition, three additional and subsequent articulations will unfold in the co-working spaces: as part of the MAD parcours, in November 2025 (with Jofroi Amaral, Deborah Bowmann, Eléonore Joulin, Valentin Souquet) in December 2025 on the occasion of the fourth edition of BXMAS-ART, and in February 2026, in the context of the PhotoBrussels Festival.

Developing a project for and with a collection is always a specific exercise as collections often reflect a mediated, indirect reflection of taste and sensibility, and of a personality that creates and gradually articulates its discourse through the evolving development of the collecting adventure. Sub specie, I have always appreciated the character of Frederic de Goldschmidt’s collection, coherent, eclectic (in the etymological sense of the word, from greek eklegein = to choose), as well as the direct support he often offers to emerging artists, working in close dialogue with them, helping to produce new works, even when that doesn’t necessarily mean acquiring them right away. In the ideal cases, the discourses elaborated through the process of collecting write themselves beyond the influence of the market and galleries, without denying or sidestepping though those realities of the art world. Frédéric de Goldschmidt is, of course, deeply familiar with the mechanisms of the market and the subtle puzzle of interactions and opportunities, sometimes random, that lead to the valuation of a work of art. Even if, unlike Midas, not everything he touches turns to gold, he is fully aware of the role that he, like other key players in the art world, can play in the recognition and valuation of an artist’s path. In this sense, it seemed to me that Cloud Seven, and the interaction with Frédéric’s collection, could offer the ideal context for developing an exhibition project which I had been carrying with me for some time — (NOT) ALL IS GOLD. Subverting the trans-idiomatic expression in English (but also in French, Italian, etc.) saying that “all that gliters is not gold,” the title suggests, conversely, that everything might be or become so. Overall, the exhibition questions the notion of value and value creation in art, whether intrinsic or metaphorical, subverted or arbitrary, quantitative or qualitative. Several thematic threads emerged clearly in the selection of works: Alongside works that embrace or subvert the precious/poor nature of their constitutive materials, other creations subtly comment on the ultra-liberal economic world, and more specifically, on the art market economy and on the status of artists, as well as the strategies artists employ to ensure their survival. A particular attention has also been given to works that integrate transactional reflection and mechanisms into their creative process, often by involving the collector or patron directly. Finally, a specific articulation explores the notion of otium liberale (liberal leisure), as a way to resist economic diktats.

51 artists:

Ignasi Aballí, Jacques André, Elena Bajo, Béatrice Balcou, Eva Barto, Thomas Bernardet, Alighiero Boetti, Kasper Bosmans, Aline Bouvy, Jérémie Boyard, Emilie Brout & Maxime Marion, Marc Buchy, Carlos Bunga, Julian Charrière, Magnus Frederik Clausen, Vaast Colson, David de Tscharner, Daniel Dezeuze, Nico Dockx, Laurent Dupont, Teresa Estapé, Cristina Garrido, Filip Gilissen, Valérian Goalec, Fernanda Gomes, Ferenc Gróf, Wade Guyton, Jan Henderikse, Ana Jotta, Ermias Kifleyesus, Gabriel Kuri, Pierre Leguillon, Tom Lowe, Karine Marenne, Céline Mathieu, Diego Miguel Mirabella, Jonathan Monk, Giovanni Morbin, Sophie Nys, Puppies Puppies, Emile Rubino, Kurt Ryslavy, Matthieu Saladin, Ilona Stutz, Egon Van Herreweghe, Chaïm Van Luit, Laurence Vauthier, Pieter Vermeersch, Oriol Vilanova, Andy Warhol, Elsa Werth.

Ground Floor

Сombines a series of works that illustrate in an organic sequence the different areas of investigation of the show. Highlights, all pushing and challenging common assumptions and perspectives, are lithographs by Wade Guyton printed over a 1928 Manet exhibition catalogue from the Matthiesen Gallery in Berlin (which included a painting acquired by Frédéric de Goldschmidt’s grandmother and whose sale served as foundation for his collection of contemporary art), Jacques André’s unemployment stamp canvases commenting on the artist’s precarious status, Marc Buchy’s speculative labor contracts, Teresa Estapé’s diamond stripped of commercial worth and Giovanni Morbin’s performance documentation asserting idleness as political resistance.

Displayed on a small shelf, Cristina Garrido’s Unholy Alliance: ARTFORUM (February 2012) shows the spine of the art magazine, and behind it, two compacted papier-mâché balls: one small, made from editorial pages; the other, significantly larger, from the advertising sections. A wall display shows the five spirit levels placed by Laurence Vauthier during her performance Added Value, commissioned and acquired by Frédéric de Goldschmidt. The final price of the work was based on how long the artist maintained ...

First Floor

Brings together works that primarily articulate their critical dimension with regard to the notion of valorization of the work through its very materiality, whether via its technique, support, or processual history. The first work encountered on the stair landing is a highly minimal and historic piece: Châssis avec film plastique transparent (1968) by Daniel Dezeuze, one of the founding members of the Supports/Surfaces movement. Taken literally, it represents a kind of zero degree of painting, and the piece subtly echoes Ignasi Aballí’s work on the ground floor.

The material most commonly associated with financial value, paper currency, becomes the raw, denatured material of Shredded Value, a work by the Dutch artist Jan Henderikse, which here takes on the appearance of a quasi-vegetal carpet. Egon Van Herreweghe’s contribution, drawn from his Grand Cru series, takes the form of a box for a bottle of Château Lafite Rothschild, 1976, a choice that is, of course, far from incidental. Inside, in place of the bottle, is a photographic print of it developed on unfixed baryta paper. In other words, should the fortunate owner of this grand cru facsimile decide to open the box to better enjoy it, the paper would blacken and the print...

This invitation to slowness acts also as an exhortation, a metaphysical awareness of the cycles of life, of nature, of civilization, and a memento of our shared condition as beings, objects, or artifacts, all ultimately destined for decay, disappearance, and forgetting. This quasi-curatorial artistic practice applies particularly to Recent Painting, which we present here. At its core, it is a page from a damaged catalogue altered by water and time devoted to the American painter Agnes Martin. This reproduction was collectively restored by the artist in collaboration with students from the restoration department of La Cambre. In doing so, the reproduction becomes an original work in a way, that is created through a process of co-authorship, thereby acquiring the specific valorization of a unique artwork. Its detailed caption informs the viewer about the material history of the piece, foregrounding the collective chain of creation and thus the intrinsic value augmentation at the heart of all acts of creation.

Second Floor

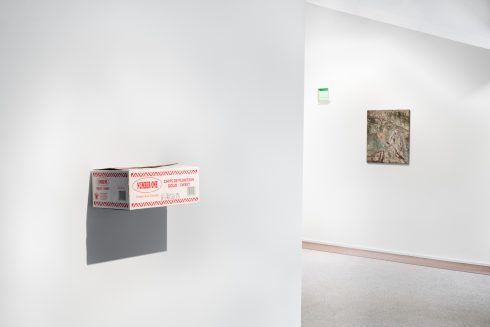

Here the focus shifts to works that directly engage with the economy of the art world, transactional protocols, and the status/economy of artists themselves. On the landing, a very simple and effective neon by Jérémie Boyard.. Its angular and sketchy outlines are directly taken from a graphic that highlighted discount prices in a supermarket leaflet, cut in half and empty. Originally conceived for an exhibition in Greece, Debt Is Only a Promise (2016) by French artist Matthieu Saladin has been updated for the occasion in Belgium’s three national languages. Each of the three stamping presses features the eponymous phrase in one of these languages, denouncing an economic system that is largely based on the involuted financing of national debt. In front, Gabriel Kuri’s Untitled (Symmetry of Choice) acts in this context as subtle comment on his own economy, a recurrent feature of his body of work, and on the polyfunctional character of Cloud Seven: a notice board is defunctionalised serving as letters are replaced by small salt and pepper packets, collected by the artist over his professional travels. Sophie Nys presents a photograph of the Tour du Midi, an emblematic tower housing the Federal Pension Administration. The photograph (a ...

Third Floor

The third floor successively calls forth themes of consumption, leisure, and even idleness, ultimately guiding us toward the notion of rest and a more permanent state of non-productivity.

Facing the staircase is Compro Oro, a double-layered engraved Plexiglas piece by Ilona Stutz, whose title acted as a trigger to the concept of this exhibition: it reproduces, with minimal stylization, a pawnshop/jeweler’s sign from Rome’s famous Via Merulana.

Beside it, a striking example of Campbell Soup, screen-printed, as it should be, on a cardboard shopping bag by Andy Warhol, the iconic godfather of conceptual Pop Art. The choice of support here mirrors the very question of elevating a highly ephemeral and symbolically domestic consumer item to the status of artwork. This proximity is especially resonant for Jacques André, for whom Warhol was undoubtedly a guiding figure in the

early stages of his career. As previously mentioned, André has long embraced, both aesthetically and politically, the statu...

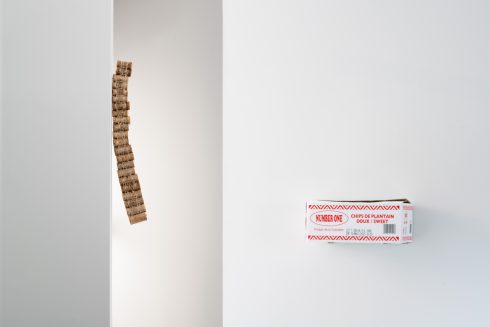

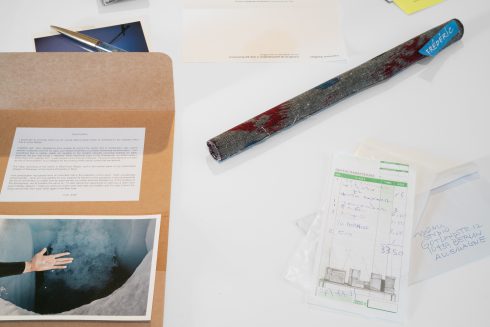

as a welfare recipient has been seminal in shaping several of his creative projects and protocols. This is especially true in his repeated purchases of identical objects (books, records, and other cultural prod ucts). Using his own terminology, these ARTERS (« achats à répétitions, tentatives d’épuisement et reconstitution de stocks ») are described as the result of an “extremely slow and complex” process, shaped by circumstance. They form a clear critique of the compulsive consumerism imposed on the citizen, and, even more so, on the unemployed person. In doing so, André also counterfeits the logic of financiers and speculators: by creating artificial scarcity on the market, he hopes to indirectly profit from the rising value of these items on the secondhand market. This particular ARTER centers on the purchase of a record by CAN whose very title, I Want More, acts as a direct and ironic echo of consumer and collecting drives. In the copies we unpacked from their box, we sought to highlight and verify the validity of the artist’s theory. The way this work entered Frédéric de Goldschmidt’s collection is also noteworthy: he received it as a token of thanks for the financial support he gave to Jacques’s (non)-gallery — stand at Art Brussels in 2022. A similar logic of gratitude in exchange for financial backing underpins the nearby presence at the foot of the staircase leading to the terrace of Filip Gilissen’s photographic print It’s all Downhill from Here. On a view of Rotterdam is juxta posed with a golden slope, referencing a performance in which the artist suspended the eponymous sculpture (here represented by a small keychain) from a crane, a gesture evoking the decline of a society consumed by its fascination for “glitter”.

Stay in the loop.

Events and exhibitions straight to your inbox

By clicking send, you’ll receive occasional emails from Cloud Seven. You always have the choice to unsubscribe